A Conversation in Steel

Fencing has experienced a renaissance in the US, yet few understand what the sport is all about. On the 130th anniversary of the US Fencing Association, a veteran guides you through the basics.

by Missag Hagop Parseghian, PhD (Copyright 2021)

Gladiatorem in arena cepere consilium – The swordfighter reveals himself only when he gets to the arena. Lucius Seneca1

Fourteen meters, just 14 meters is all you get. When facing your opponent, sword in hand, your area of combat is the length of a semi-trailer truck or a Spinosaurus. No castle walls, theater balconies or chandeliers to swing from. Perhaps a bit cramped when compared to a pitch or a court; believe me an Englishman and Scot at Stirling Bridge or Persian and Armenian at Avarayr would have relished 14 meters between themselves at the height of battle to wield swords unencumbered.

During the Olympics, you might glimpse the wielding of swords on the fencing piste and wonder “what the heck is going on?” The action moves rapidly, often too quickly to make it telegenic for the casual viewer. The instant replay must always be slowed down. The uninitiated are often stunned at the ability of fencers to observe an entire “phrase” (that’s what we call the series of actions during an encounter) and interpret the sights and sounds of clanking blades into a coherent picture of what happened and who is awarded the touch. The slash of a saber or the flick of a sword’s tip are the second-fastest moving objects in sport only eclipsed by the speed of a bullet at a shooting competition. With repeated observation over time, the eye becomes accustomed to the speed and actions appear to slow down. I’ve had plenty of opportunity to acclimate to the speed. As a co-founder of the South Coast Fencing Center (SCFC, established 1999 www.southcoastfencing.com ) in Orange County, California, I have been dueling with steel blades since the Olympics last visited my hometown of Los Angeles in 1984. And I’m not alone.

Established in 1891, the US Fencing Association (USFA www.usafencing.org) has over 40,000 members according to Bob Bodor, the USFA’s Member Services Director. When it was first started a 130 years ago by a group of New Yorkers as the Amateur Fencers League of America, fencing was as popular in North America as it was in Europe. Then it receded from view for decades given the opportunities children had participating in high school team sports with significant scholarship programs for college. I picked up the sport where most fencers did in the past two centuries. When Karl Weierstrass, the father of modern mathematical analysis, went off to college in 19th Century Germany, his father urged him to study law and business; he focused on math, beer drinking and fencing. How history can repeat itself. When I went off to UCLA, my dad hoped for a lawyer and businessman, I studied science, beer drinking and … fencing. He has my mother to blame, since it was she, a woman born and raised in suburban Boston, the epicenter of American collegiate fencing for decades, who first encouraged me to try the sport I will most likely spend the rest of my life participating in.

What has been surprising for the last 30 years is the renaissance the sport has experienced particularly with young kids. Some of it can be attributed to fencers teaching their own children the sport they love, but the proliferation and increased accessibility of fencing clubs across the US must also be attributed to the flood of foreign coaches that arrived to our shores after the collapse of the Soviet Empire, enriching the variety of training methods available to students. In my opinion, this tends to mirror the rise of fencing in the US and Canada in the late 19th Century, which was accompanied by the rising tide of immigration from Italy, France, Germany and Spain. While this rebirth of fencing in the US is driven by those youthful in body, there is a significant participation by those youthful in mind and more mature in age. Fencing is the one sport where an 80-year-old can trounce a 15-year-old and walk off with a gold medal. The sport where quick thinking is as important as physical agility.

Agility of Mind and Body

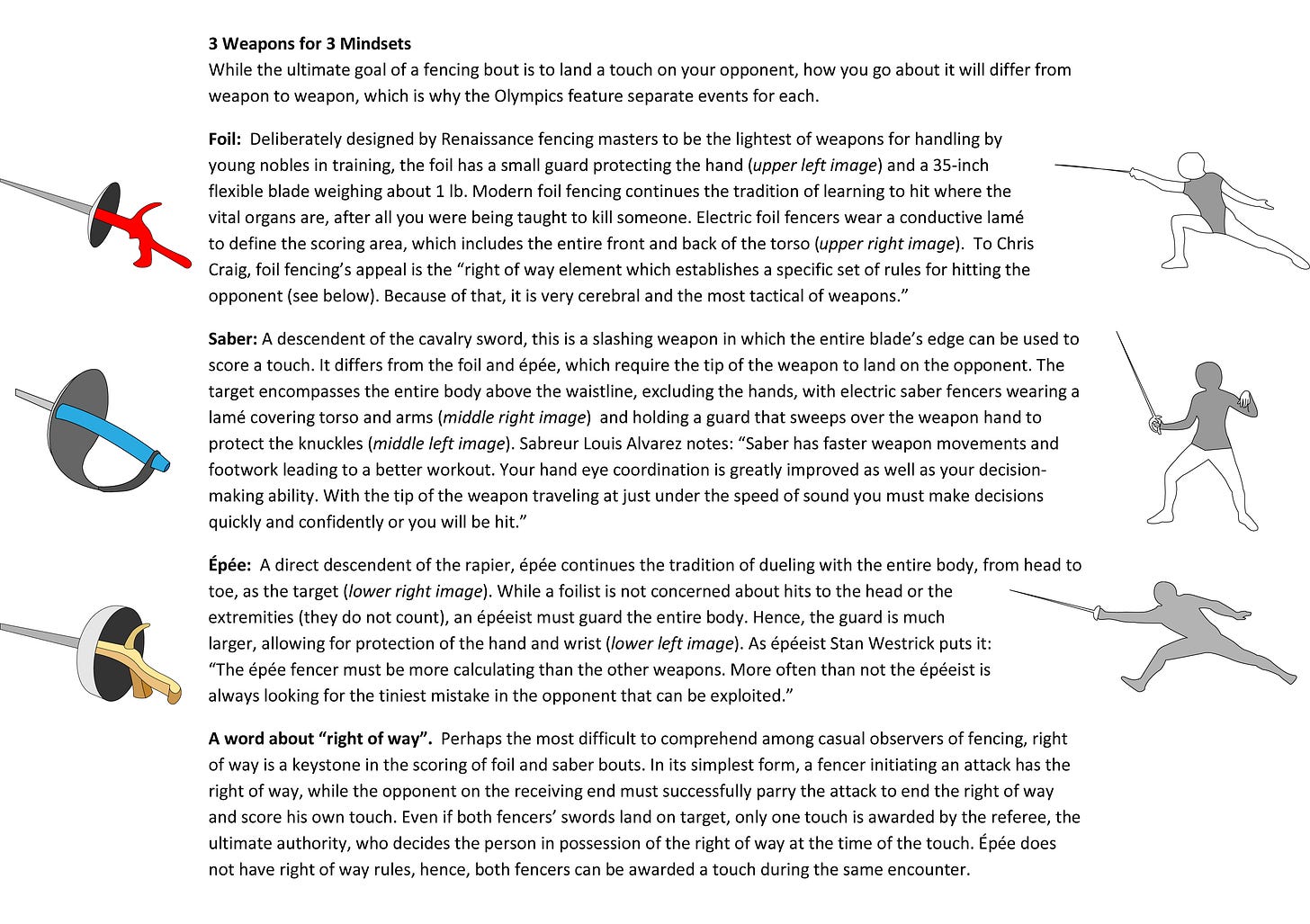

Fencing is categorized into three separate weapons: foil, épée and saber. Historically, each weapon had a different purpose. These differences have carried over into the modern sport and affect how each weapon is used (see 3 Weapons for 3 Mindsets). Regardless of the weapon, fencing can simply be described as one opponent trying to find an opening to “touch” the other. The one about to be touched must get out of the way or, more often, block the attack (referred to as a “parry”). If the defender were to successfully parry the attack, they will quickly launch their own attack (referred to as a “riposte”). While the tactics may have changed over the millenia, the actions themselves are much like those first illustrated in Egyptian hieroglyphs.

When teaching, I have often likened the continuous action between two fencers of parry, riposte, counter-parry and riposte as a conversation in steel…what matters is who gets the last word. It’s a very athletic conversation. “Fencing skills are life skills. On the intellectual side, students develop a strong sense of concentration and focus, determination, analytical thinking, goal-setting and the ability to remain calm and composed under pressure. On the physical side, fencing is a very well-rounded sport which develops quickness, flexibility, coordination, strength and cardiovascular conditioning, with the most important quality being coordination,” states SCFC co-founder and Head Coach Brenden Richard. Three-time US National Champion and Coach Clinton Kershaw emphasizes, “fencing, in each of the three styles, develops physical abilities such as hand-eye coordination and general athleticism. Because the sport requires a fair amount of physical exertion, fencing is a great way to improve general fitness.”

The benefits of the sport are as cerebral as they are physical. Fencers often refer to their sport as physical chess and Cornell team alumna Dr. Lucia Rafanelli explains that thinking the best: “Before I started to fence, though I understood the concept of ‘being a few moves ahead’ in chess, for example, I couldn't even begin to imagine how to make it happen. But as a fencer, you need to continually plan moves and counter-moves, anticipate your opponents' moves, induce them to make the moves you want them to, and adjust to changing circumstances at a fast pace. I'm no Clausewitz, but once I started fencing, the mode of thinking that makes strategy possible suddenly became clear to me.” And as foil fencer Chris Craig eloquently sums it up, “The essence of fencing: you observe your opponent and develop a strategy to use their habits and quirks against them.”

Chess is only a partial analogy. It’s part chess…part poker. Fencing is just as much about not telegraphing your intentions, indeed, lying to your opponent about them. The battlefield, a narrow strip only 1.5 meters wide and 14 meters long, is the crucible where you combine physical and psychological warfare much the same way your ancestors did when facing each other in single combat. As épéeist Stan Westrick puts it, “I tell my students that one of the greatest things about fencing is getting into your opponent's head. By that I mean making your opponent do what you want them to do.”

Fencers often refer to their sport as physical chess. Chess is only a partial analogy. It’s part chess…part poker.

What’s the benefit of being on the receiving end of those head games? “A unique aspect of fencing is learning ‘grace under pressure’. To execute your actions you have to tame the adrenaline and think clearly” explains foilist Michael Kuzmak. Sabreur Edison Leung elaborates, “One of the biggest benefits of fencing that I realize now is that fencing teaches you resilience. This is really important today for kids. From psychologists to college administrators, they continually remark that kids today lack resilience. Fencing teaches it in spades. You face hits mentally and physically. You can be utterly devastated in a bout and sooner or later fence that person again. And again.”

As Coach Jaime Wood puts it: “People who stick with the sport long enough gain the ability to read other people via body language as well as by analyzing their prior performance. They learn how to remain calm under daunting and stressful situations, and to continue to think even if they are outmatched. They learn to critically think about the bout afterwards to analyze what went wrong and what they can learn from their mistakes. In fencing you have to treat defeat as a learning experience, something to grow from, and a wise person takes these lessons and applies them to their everyday life. Just like fencing, self-analysis isn't easy, but I guarantee other people take notice of this ability and it helps you stand above the crowd.” He adds, “More than anything I love the thought that goes into each bout, and the athleticism that goes into putting a plan into action. Both thought and body have to be in balance for things to work out.”

A Sport for All Ages

It is never too late to start fencing and most clubs offer lessons to kids well past their college graduation. In 2012, Italian researchers studying the effects of fencing in older individuals found the fast decision making required for the sport helped improve neural processing and visual attention, traits that decline with aging. Given the large percentage of young fencers who remain with the sport or return to it as they get older, it should not be surprising that the USFA National Championships every year also run “veteran” tournaments for participants 40+, including ones specifically for the 80+ age group. “I started fencing when I turned 57”, remarks foilist Jeff Keeney, “and this year I am going to the National Championships to participate in the Veterans events.”

While many colleges offer classes for their students, I really had more time to devote to the sport once I got into my PhD program at UC Irvine. Over the years, the club had its fair share of PhD candidates in the sciences. Hitting someone other than your thesis advisor with a 35-inch blade gets your mind off the failed experiment sitting in the lab. Contrary to my own start, nowadays many serious fencers get started before they hit the ripe old age of 10. Some parents bring their kids knowing nothing about the sport themselves, while others hand down the love of fencing like a family heirloom. “I first got interested in fencing because of my mom. Mary was a fencer in college, so I grew up hearing stories about her under-funded Division III team at the Stevens Institute of Technology consisting of full-time engineers and only-part-time athletes aggravating giants like Ohio State University with their unexpected success,” says Rafanelli, who is now an Assistant Professor at George Washington University. For those individuals unfamiliar with the sport, I have often had parents learn to fence right along with their kids. “My father would sit with me under the tree in our backyard and read me stories about Robin Hood and King Arthur, so I always wanted to try fencing. When I was 16, my dad suggested we try it in the next town over. We did that for a couple years as a father-son activity,” recalls Kuzmak.

Greg Procopio started out as the parent of a fencing kid, regularly taking his daughter Lucia to class. “Soon I realized it was a fun way to get exercise, so I started to take classes as well.” Father-daughter competitors make for an interesting dynamic. “When we fenced each other, she wasn’t happy when she lost to me. And once when we were in a USFA competition facing each other, I was a little conflicted about trying to beat my own daughter, but that did not matter since I did not hold back and she still clobbered me.” Greg continued, “Lucia was fencing for Northwestern University. On a visit, I took my gear and was fencing at a tournament there. It’s a nice feeling having your daughter cheering you on. I still have the chart from my daughter’s first gold medal victory on my work desk. We are so different that if we hadn’t done fencing I don’t know what we would have in common.” Today Lucia Procopio is the Assistant Fencing Coach at Wayne State University, a coach at the Renaissance Fencing Club in Michigan and a Central Collegiate Fencing Conference Assistant Coach of the Year.

For Nouneh Assadourian, fencing is more than a casual father-daughter activity since her father, Olympian Sarkis Assadourian, coaches her. “In Iran, he was not allowed to train me. When we first arrived in the US, he would give me lessons in the garage. Once he established himself in the US, he would coach me at the local clubs.” As a competitive épéeist who recently joined the Armenian National Team, she trains every day; fencing 3 times a week and cross-training on the other days. “My goal is to be an Olympian like my dad, and my dream is to fence professionally someday.”

Épéeist Jerry Yang remembers, “I started fencing in high school my junior year. A friend’s mom came to a group of us playing Dungeons & Dragons and asked if we wanted to ‘learn to fence and to play with swords’. This was my chance to experience ‘swashbuckling’ through the foil classes with Salle Templar. Back then I chose the California State University at Long Beach because of the engineering program, but it was a plus they had a successful NCAA fencing program.” While many SCFC alum have gone on to top schools with strong fencing programs, Cornell, Columbia, Northwestern, Vassar and Princeton, to name a few, don’t sign your kid up expecting to get a fencing scholarship. Those are few and far between. But listing fencing on the college application does not hurt and many young fencers end up on the team at their respective schools. Just as important, they end up joining a community they will likely be part of for the rest of their lives.

Holding Tradition in Your Hands

And then there is the history. As Craig puts it, “There is a romanticism that comes with fencing. Even the rule book is imbued with tradition.” French and Italian terminology dominate the language of fencing. There are the salutes that come before and after an encounter (and in the middle of a bout if the scores reach sudden death, we call it La Belle Touche – the beautiful touch). There are the weapons themselves. Richard Cohen, 5-time UK saber champion, tells us the word “sword” is derived from the Old English sweord, itself derived from its Indo-European root meaning “to wound” (By the Sword 2003 pg.104). The modern saber is a slashing weapon descended from the cavalry sword, yet the actions taken with it are ancient.

You would think the link between swords and their sharp tips would naturally suggest thrusting the weapon into your opponent would be a crucial skill to learn. Armenians don’t even make a distinction between “sword” and “sharp”, using the same word soor (սուր) for both over the millenia. Thrusting was a concept unknown to the Romans until they learned it the hard way in combat against the Spaniards and their iron swords. The modern “thrusting” weapons in our sport are the foil and the épée. The foil has a target area focused on the torso, the area where the vital organs are (apparently there are no vital organs in the head). In contrast, the épée is a true dueling weapon that targets the entire body; in fact, Duelling Swords was the term used in the USFA rules until the name was changed to épée in 1915.

Even the salle may be immersed in tradition, though you may not know it from the look of the place. The word reminds us of the days when French masters gave lessons in their salons (living rooms). Too many movies portray a salle with hardwood floors, marble busts and wood paneled walls decorated with weapons and pictures of the club’s champions. Sans the wood paneled walls and marble busts, SCFC has those things in its 5,000 square foot space, but they fade into the background in a modern sport that requires electronic scoring systems mounted on the walls and ceilings. If you choose to attend a class at your local park & rec, you would be harkening back to a time when Romans studied swordsmanship at the Campus Martius and the other 7 parks of Rome (The Book of the Sword 1884 pg. 249). During my years fencing as a graduate student at UC Irvine, we were relegated to a theatrical stage. Perhaps a historically fitting location given that one famous Roman salle d’armes was located in the Amphitheater. Not being a priority sport, like volleyball, the University often forced us to find alternative venues. My favorite, the roof of an apartment a fellow fencer rented on the Balboa peninsula in Newport Beach; while the fencing space was a bit confining (over-running the strip could lead to a 3 story fall on to Balboa Blvd.), the views of the yacht harbor and the Pacific were spectacular.

While swordsmanship reaches back into antiquity, the modern art of fencing came to fruition in the Renaissance, when the accessibility of the Gutenberg press allowed for the dissemination of treatises by Achille Marozzo (1536), Jeronimo de Carranza (1569), Joachim Meyer (1570) and Henry De Sainct-Didier (1573), establishers of the Italian, Spanish, German and French schools of fencing, respectively. The tactics described in those and other Renaissance texts are still studied and practiced by Historical European Martial Arts (HEMA) clubs. Unlike the modern sport of fencing, which is constantly evolving its rules to adapt to advancements in training and technology, HEMA practitioners are ensuring classical and renaissance knowledge of swordsmanship is not lost. Studying the old texts provides one with an interesting perspective according to Coach Jonathan Mayshar, one of the founding members of the HEMA Alliance and its former President. “The more you study swordsmanship and other medieval weapons the more you see the similarity of the schools and even the similarities to other martial arts.” Mayshar also points out: “Contrary to Hollywood movies, even during the Middle Ages there were extended periods of peace in parts of Europe. During those periods, swordsmanship was studied because it was just plain cool, rather than a response to an imminent war.”

But who’s going to watch a Hollywood movie about times of peace in the Middle Ages? Long before Brit Bob Anderson was training actors to handle swords…uhh, light sabers…in Star Wars, it was the Belgian Fred Cavens and American Ralph Faulkner who were coaching actors and staging fight scenes in a long list of movies during the golden age of film. Faulkner, an Olympian, went on to establish his own salle in Hollywood, Falcon Studios. “I went to his studio several times in the 1970s,” Westrick remembers. “His studio was very unassuming from the street. Once you stepped inside it felt like the main hallway at one of those 1930s era movie studios. You could not see the walls because they were covered with photos of movie star alumni. The hallway opened up into a court yard with little buildings on each side. You could look inside and see actors practicing their scripts. At the far end of the court yard was the salle. It had double doors and when you walked in there were fencers drilling, some in group lessons, and others taking lessons with Faulkner's assistant or with the Fencing Master himself. His assistant looked like someone out of central casting. He had shoulder length dark hair kept in place with a bandana. He also sported an eye patch. His job was to get you ready for your eventual lesson with the Master. Once you were ready, he would send you over to Faulkner, who was ‘old school’ with his lesson. By that I mean all of his directions were in French.”

There is a romanticism that comes with fencing. Even the rule book is imbued with tradition. Chris Craig

Those of us who are ‘old school’ first started out learning the basics (advancing, retreating, parrying and riposting) using a foil, the weapon designed by Renaissance masters to be lightweight for young nobles to handle. We would then choose to go on as competitive foilists or, once grounded in the basics, we could apply that knowledge as we studied the épée or saber. Today, the choice of weapon you start training with may depend on which club you attend. While coaches who are considered fencing masters have the expertise to train you in all three weapons, only a few clubs have such broad programs with most opting to specialize. Amusingly, this has resulted in the emergence of three separate sub-cultures among fencers, each testifying to the superiority of their beloved weapon. “I love saber. In saber you can cut and slash as well as hit with the point. Defensively, attacks can come from many directions, making it challenging while expanding your peripheral vision” says Leung. “People tend to be pretty rah-rah for their weapon but after fencing for a while you appreciate the exquisiteness of each. One of the nice things about fencing is that after being competent in one weapon, you can enjoy fencing with the other two.” His words reflect my philosophy that you find a weapon you enjoy, get a good grounding in it and then learn another or all three. It’s no fun dropping into a club one night and finding out they are not fencing “your weapon”.

With the wide-spread use of gunpowder, fencing evolved from a necessary form of self-protection into a sport for the nobility. Swordsmanship was already considered a necessary pastime in the development of young leaders when, in the 19th Century, fencer Baron Pierre de Coubertin founded the modern Olympic games and ensured the sport would remain a permanent fixture at every Olympics. Today the Fédération Internationale d'Escrime (FIE, established 1913), headquartered in Switzerland, governs international fencing competitions, including the events at the Olympics. “There is no other international competition like it. I was representing Iran at a World Cup event in Austria not long before the Olympics and no one expected us to do well against the Italians. Once the bouts began, I was beating each one of them. Since the scoring machine for épée locked out the opponents touch milliseconds after my hit, the Italians were getting very frustrated that they could not land their touches in time. I knew I had gotten into their heads when they demanded my equipment be inspected. It drove them even crazier when officials told them I was not cheating,” remembers Coach Sarkis Assadourian a member of Iran’s 1976 Montreal Olympic team. “So, I went to Canada as part of the Iranian épée team. You know, the Italians were not happy to see me. I was beating them again, but my team lost to Italy by only one point. This shook up the Italians and they did not win any épée medals.” Assadourian’s Olympic experience illustrates what I always tell my students, part of the fun of fencing is to psychologically tear down your opponent.

One for all and all for one

“What club are you with?” I asked the guy dragging a fencing bag nearly identical to the one I have back home as we were walking near the World Trade Center on a business trip to New York. I was dressed for a business meeting, but he didn’t flinch and gave me the name, location, and as fencers usually do, invited me to drop by for some bouting. “The fencing community is a relatively small one but very close knit. You can go anywhere in the country or world and be welcomed into any fencing club,” says SCFC co-founder and sabreur Louis Alvarez. After fencing…and studying to be a restauranteur…at Cal Poly Pomona, he went to live with relatives in Barcelona for a year and joined a local club. Coach Richard studied fencing in England and Italy, while Coach Kershaw also spent time in Italy. During the Cold War, Coach Assadourian used to cross from Iran into Soviet Armenia to train. Perhaps no one I know symbolizes the international camaraderie among fencers better than Gus Cladera, Australian veterans épée champion and coach who, prior to the pandemic, flew in to train with his American friends about every other week. Working for Qantas affords him the ability to train with coaches in clubs around the world.

The proliferation of fencing clubs throughout the US obviates the need to travel long distances or even to install your own fencing salle at home, the way Theodore Roosevelt did when he moved into the White House, which he used every evening to spar with his friend Brigadier General Leonard Wood. “Keep in mind every club has its own character, a reflection of the personality of its head coach and instructors”, Craig advises. Finding the right teacher is as old as fencing itself. “Even in the Renaissance, purists decried the proliferation of ‘winkel fechteren’ (corner fencers) who had learned a few actions and were pedalling their expertise,” says Mayshar. Richard adds, “Athletes and educators each offer separate but overlapping skill sets. Fencing coaches need to be knowledgeable in current techniques, tactics and sport-specific concepts. They must also be knowledgeable in teaching methodologies, be able to connect with students and bring out their best, understand each student’s unique characteristics and be able to adjust their teaching style to best fit that student. Coaches should also connect with students and parents to develop a healthy, long term training plan that meets the expectations and resources for all involved.”

Cladera, who has studied with more than his fair share of coaches says both teacher and student must have “rapport and respect; and it’s got to be mutual. Two people cannot come together at a common goal unless they are in sync. For the fencer; you need to respect your coach's position and experience and also appreciate that he needs to earn a living...so show up to training when you say you are going to and call well in advance if you're not. For the coach (and I feel that most good coaches have this under control) understand and respect that not every student is going to be an Olympian but they still have valid ambitions which require dedication.”

"A Frenchman, who has taught him fencing, tells me that the President [Roosevelt] is a poor though enthusiastic fencer. I will not say who it was that added, ‘His natural weapon is a club.’ He seemingly takes as much joy in receiving blows as in giving them.” George Horton2 Note: The Frenchman is likely Maitre Francois Darrieult, coach at the Naval Academy and the US Olympic teams of 1920 and 1924.

Don’t settle for the first salle you visit if you feel uncomfortable. Make sure safety is of paramount importance in whatever club you choose. The last person known to have died due to fencing injuries in the US was on July 18, 1892. Ironically, he was a surgeon. As reported at the time, Dr. C.C. Terry of Falls River, Massachusetts had gone across the street to the YMCA to take his regular lesson with a Professor Castaldi when the latter’s foil broke through the mask on Terry’s face and cut into his flesh. Incredibly, the duo continued the lesson with another mask when Castaldi’s weapon broke and tore through the second mask, penetrating Dr. Terry’s brain and killing him. Today, fencers must wear multiple layers of protection with each item rated by the FIE according to the amount of force it can withstand. Today’s weapons generally have the blade made of maraging steel, a martensitic composite of iron, nickel, chromium, molybdenum and titanium that has undergone a thermal aging process to withstand stress and resist cracking. Let me take a moment to speak for every fencing coach in the world: please don’t bring a rusting weapon your grandparent used in college and ask to use it in class; the answer is NO. Before a USFA sanctioned tournament, your mask and clothing are tested by the armorer and any equipment not meeting specifications are confiscated. In that case, you have to run over to the supply stand and buy a new piece of equipment. Be aware that instructors at the club and referees at a tournament have the God given right to throw you out if they think you are not respecting safety standards. Assadourian asserts “At this moment, fencing is the safest sport in the world.” He should know, since he is a member of the FIE’s SEMI Commission, the governing body that dictates equipment safety and is constantly striving to improve it.

Even the part of the weapon that sits in your hand (the “grip”) has evolved to accommodate a more athletic game. More than once I have had someone bring me an old weapon they found with a classic Italian grip that requires a strap to keep it in your hand and ask if they can use it. It is still legal to use, but almost everyone else has moved on to a more orthopedic grip. Be aware that your right or left-handedness will dictate the handedness of your weapon, glove, underarm protector and your jacket. Even shoes were once designed for right or left-handers with greater support built into the foot from which you lunged at your opponent. With only ~10% of the population left-handed, it is important to always take the opportunity to spar with a lefty in friendly gatherings. Your entire strategy in a bout may depend on the handedness of your opponent; hence, your first encounter with one should not be in a competition when medals are on the line. That advice applies to left-handers also. As Leung, also a lefty, puts it, “Initially, fencing a lefty can be maddening but as you fence more of them, you know what works, what doesn’t, and how to be successful against them.” When training, on occasion have your coach provide the lesson as a left-hander to strengthen your game.

The rewards of coaching this ancient martial art are certainly not monetary. Getting rich teaching fencing is not likely and many instructors have other day jobs. Beyond finding the next Olympian, there are intangible rewards. Handing down rich traditions, for example. One of Yang’s first teachers was Westrick; they now often teach classes together. Or there is the moment a student begins to comprehend the ebb and flow of the action: “Some love the act of winning, while others love the act of doing, but you can see the spark in everyone's eyes as everything suddenly clicks into place. I love being there for that moment,” says Wood.

Like any sport, what you ultimately get out of it is up to you. “The more you compete the more you appreciate your individuality. You tailor your game to suit your strengths,” says Kuzmak. Cladera adds, “The most significant ‘life skill’ fencing offers is critical thinking. Being able to rapidly take in information and equally rapidly analyze all your options to come out with an optimum outcome. Sometimes I feel like I'm still working out which end of the sword to hit with. I think fencers, like golfers, have it in them that they will always be striving to improve...is that fun? I don't know...but I'm still working at it 40 years later.” So am I, and I will keep working at it. The sport whose mastery is never fully mastered until you know thy self.

How to say “Fencing” when looking for clubs abroad:

d'Escrime (French),

Esgrima (Spanish),

Scherma (Italian),

Fechten (German),

Vívás (Hungarian),

Suseramard ՍՈՒՍԵՐԱՄԱՐՏ (Armenian),

Fechtovaniya Фехтования (Russian),

Fenshingu フェンシング (Japanese),

Pensing 펜싱 (Korean).

As translated by Richard Cohen in By the Sword (2003) Publisher: Modern Library Paperback.

George Horton in The Human Side: An Estimate of Theodore Roosevelt (1904) Reader Magazine